Josip Štolcer Slavenski – Composer of the Avanatgarde forever enamoured with the Balkans

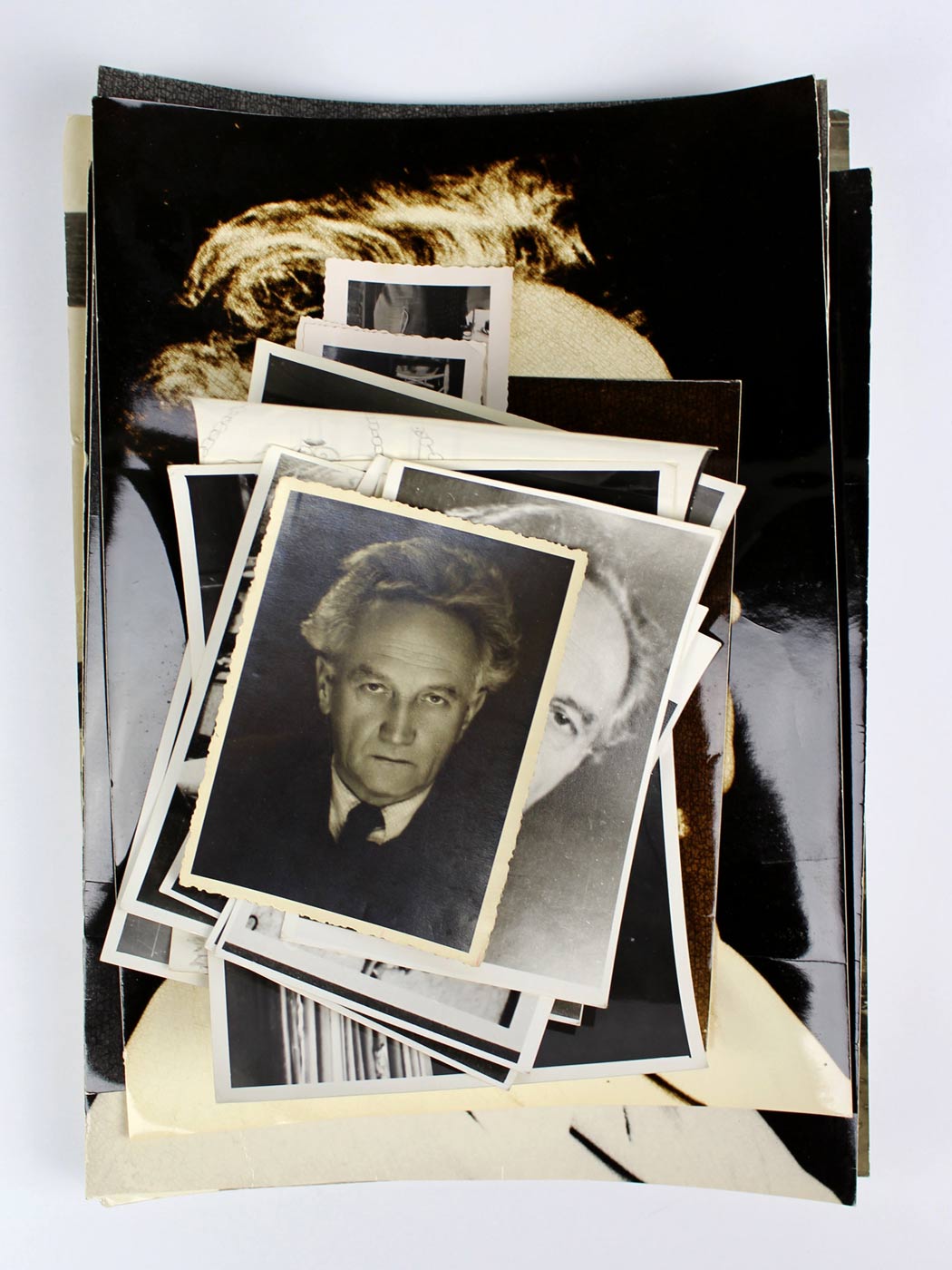

Since autumn 2015 I have been researching the life and work of one of the most important and original Yugoslav avant-garde composers of the 20th century: Josip Štolcer Slavenski.

In addition to his impressive work, what fascinates me and spurs my research is the current treatment of Slavenski by today's successor peoples of Yugoslavia. Where other nations would praise a master like Slavenski, little attention is paid to him. Actually, he is hardly known.

Born in May 1896 into a modest Croatian baker’s family in the small town of Čakovec, at that time still part of Austria-Hungary, he developed his passion for music from an early age, supported by his mother.

After studying in Budapest at the renowned Zen Academia (1913–1916), where he was a masterstudent of Bella Bartók, and graduating from the Prague Conservatory (1918–1921), Slavenski moved to the roaring Belgrade of the 1920s.

Slavenski’s work is characterised by a kind of synthesis of late-romantic pattern and contemporary artistic expression, exploring the folklore and studying electronic music and acoustic laws. The diversity of these stylistic elements determined Slavenski’s musical poetics as authentic, at that time, very modern and new.

As such, it came to misunderstandings and often contradictory critics by many contemporaries – conservatives considered his music as “chaotic” and progressives as “backward”.

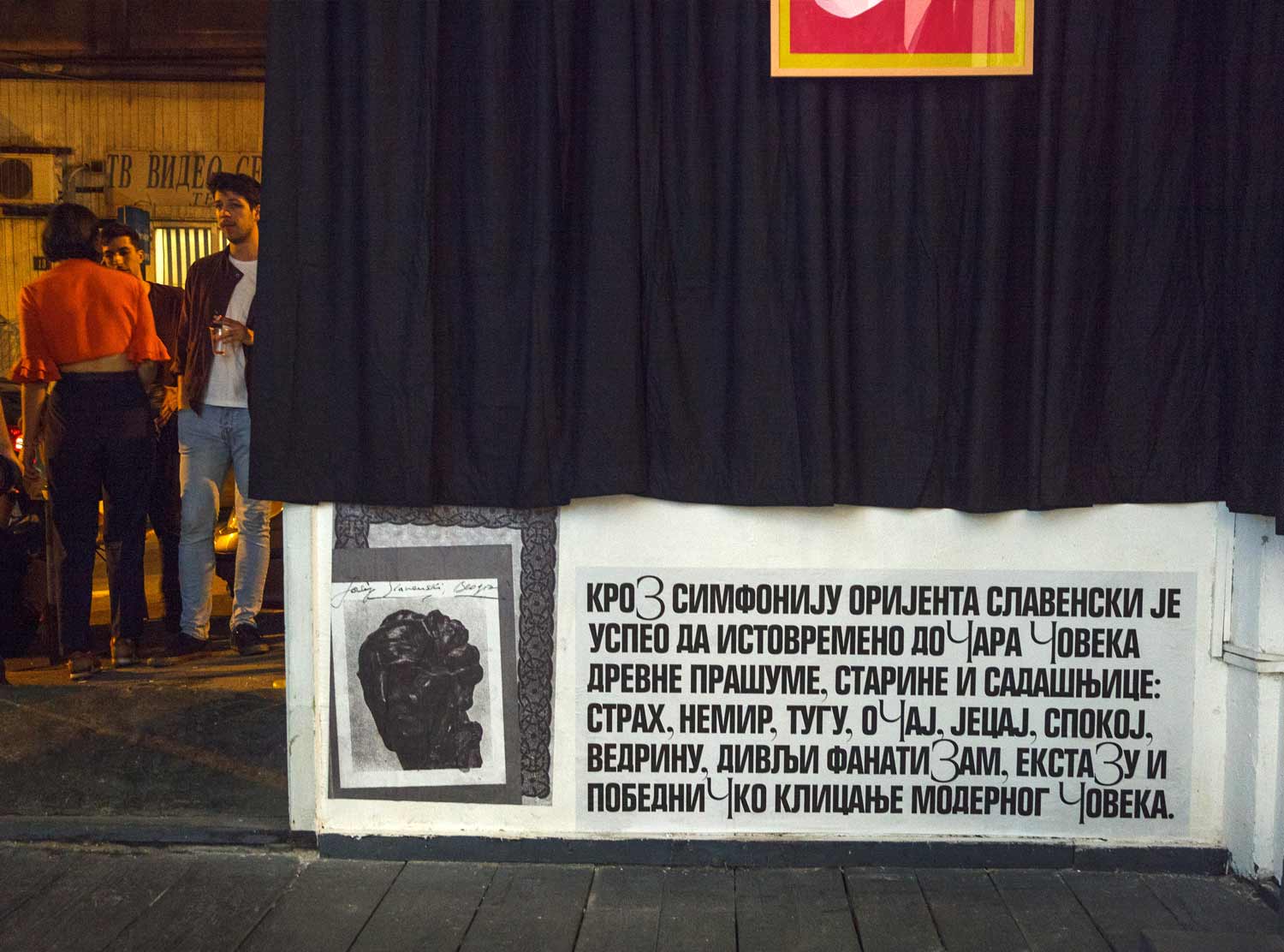

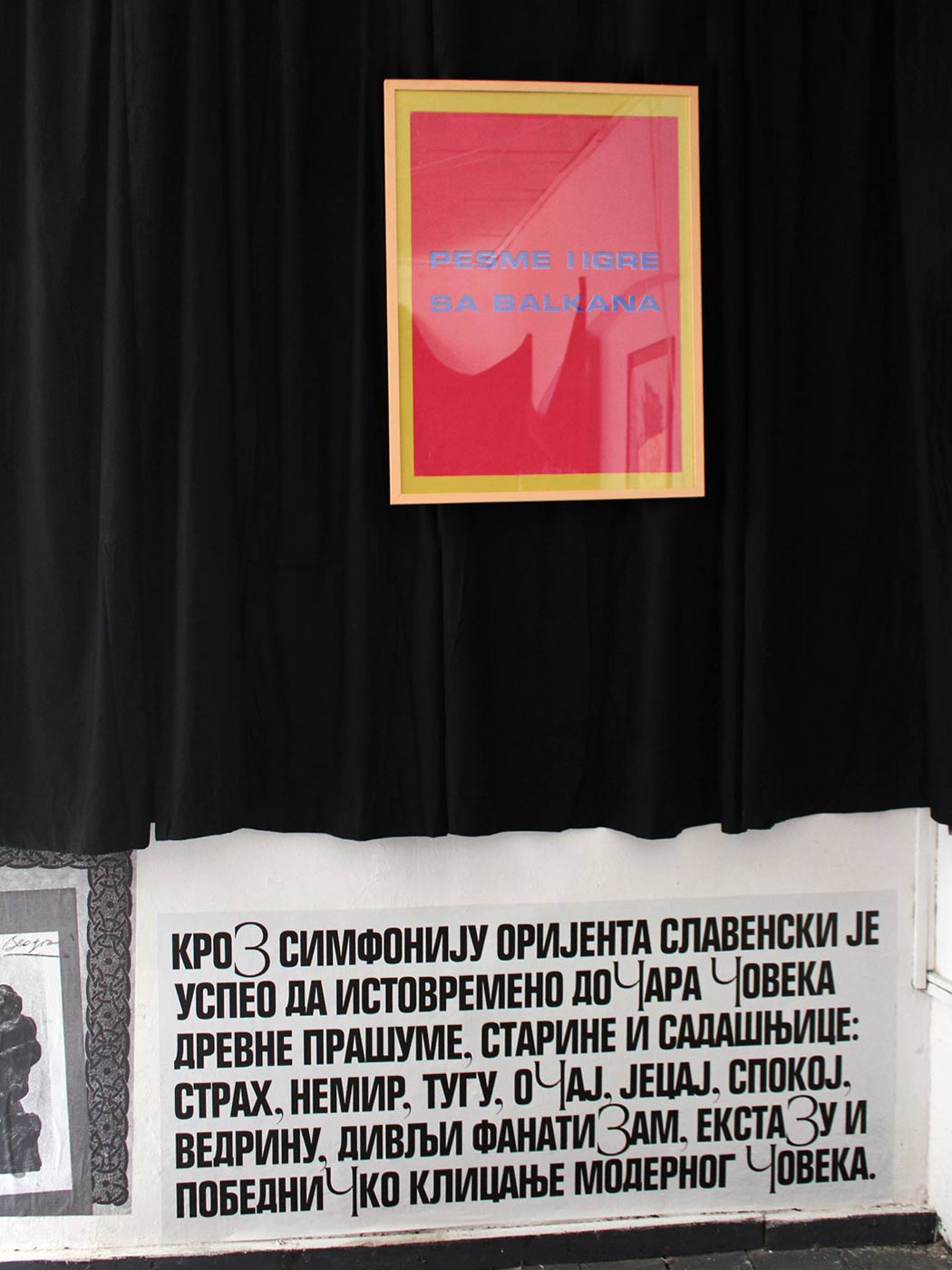

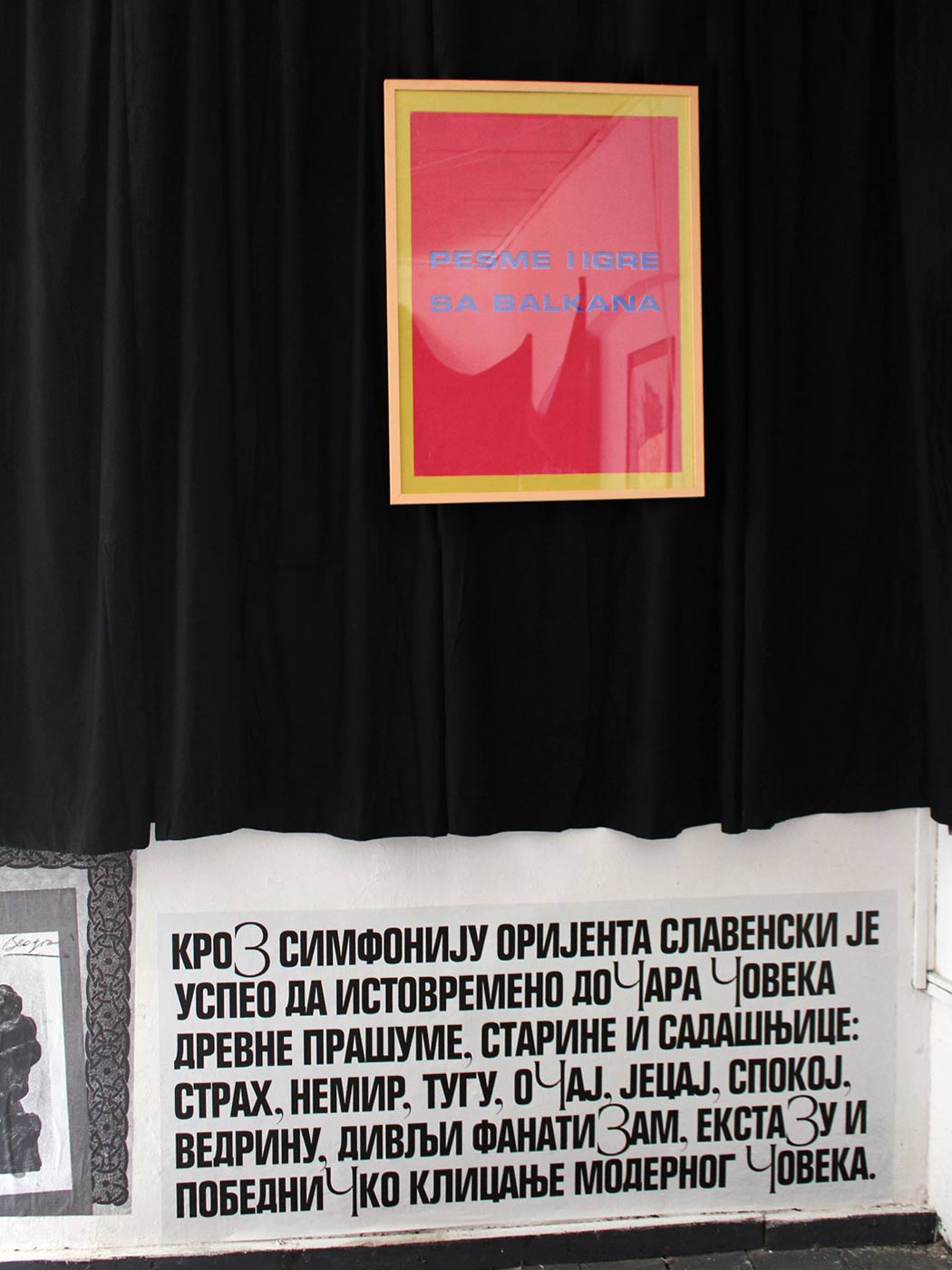

Then the capital of the newly formed state Yugoslavia, colorful, noisy, full of colors of Balkan folklore and picturesque remnants of the East, Belgrade evoked in Slaveski unlimited passion and thirst for creation. One of his greatest works were created here, such as Balkanophonia, Sinfonia Orienta, Four Balkan Games, From Yugoslavia, Chaos аnd Songs of My Mother.

Performances at the global level followed, from Berlin, Buenos Aires and Tokyo through Athens, Budapest and Vienna to Venice and New York.

He composed music for sound films of famous Prague and Berlin-based production companies, established contact with the renowned German publishing house Schott & Söhne and researched one of the first electronic music in general. Basically, he was one of the first to own a Trinitron, one of the first electronic devices that could produce music

In addition to music, he dedicated his time to science, especially astronomy, because he saw and searched a connection between cosmic currents and musical resonances. Slavenski even presented the theory of Astroakustics.

What is certainly most impressive and what makes Slavenski so unique is his approach: On one hand, Slavenski was very open to the social upheaval of European modernity, on the other hand, he was in love with the diversity and ancient folklore traditions and customs of the Balkan peoples. With this as a starting point, Slavenski created until then completely new and unusual works which, at first, meet with misunderstanding and often contradictory assessments by a large number of contemporaries.

With the end of the Second World War and the emergence of a socialist Yugoslavia, new ideologies were adopted with euphoria, which no longer fit into pre-war modernity on the one hand and the traditional Slavic approach on the other.

Works were created in the spirit of socialism, but he quickly withdrew and stopped composing. He died on November 30, 1955 in his home in Belgrade.

After his death there were attempts to revive his work, but that never reached the level Slavenski deserved. Most of these remained at the local level. With the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Slavenski was finally forgotten / consciously ignored. Because a man born in today's Croatia, who supported the empantipation and unification of the South Slav peoples and who spent most of his life in today's Serbia, did not fit into the concept of the newly formed states.

Since 2021, a website has been dedicated to Slavenski and his work.

This dilemma of the forgotten maestro piqued my interest all the more. I began my research work in 2015 in Slavenski's hometown of Čakovec, where I got access to a considerable collection of his work at Međimurje County Museum. I later got in touch with the Serbian Music Association in Belgrade, which keeps and administers his entire legacy. As an artist, I don’t want to stop at theory or research, I started to organize an event every year for Slavenski’s birthday on May 11th.

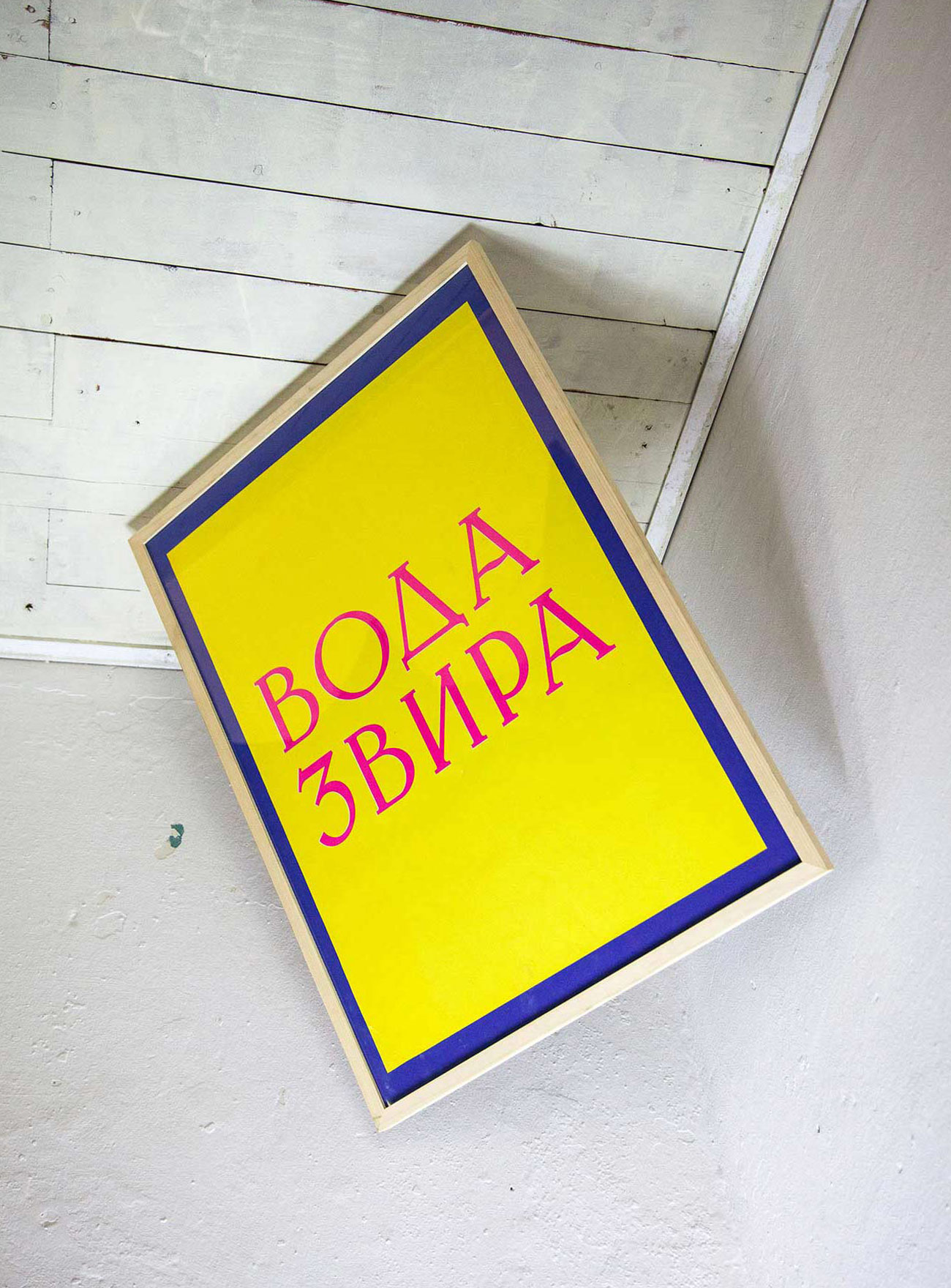

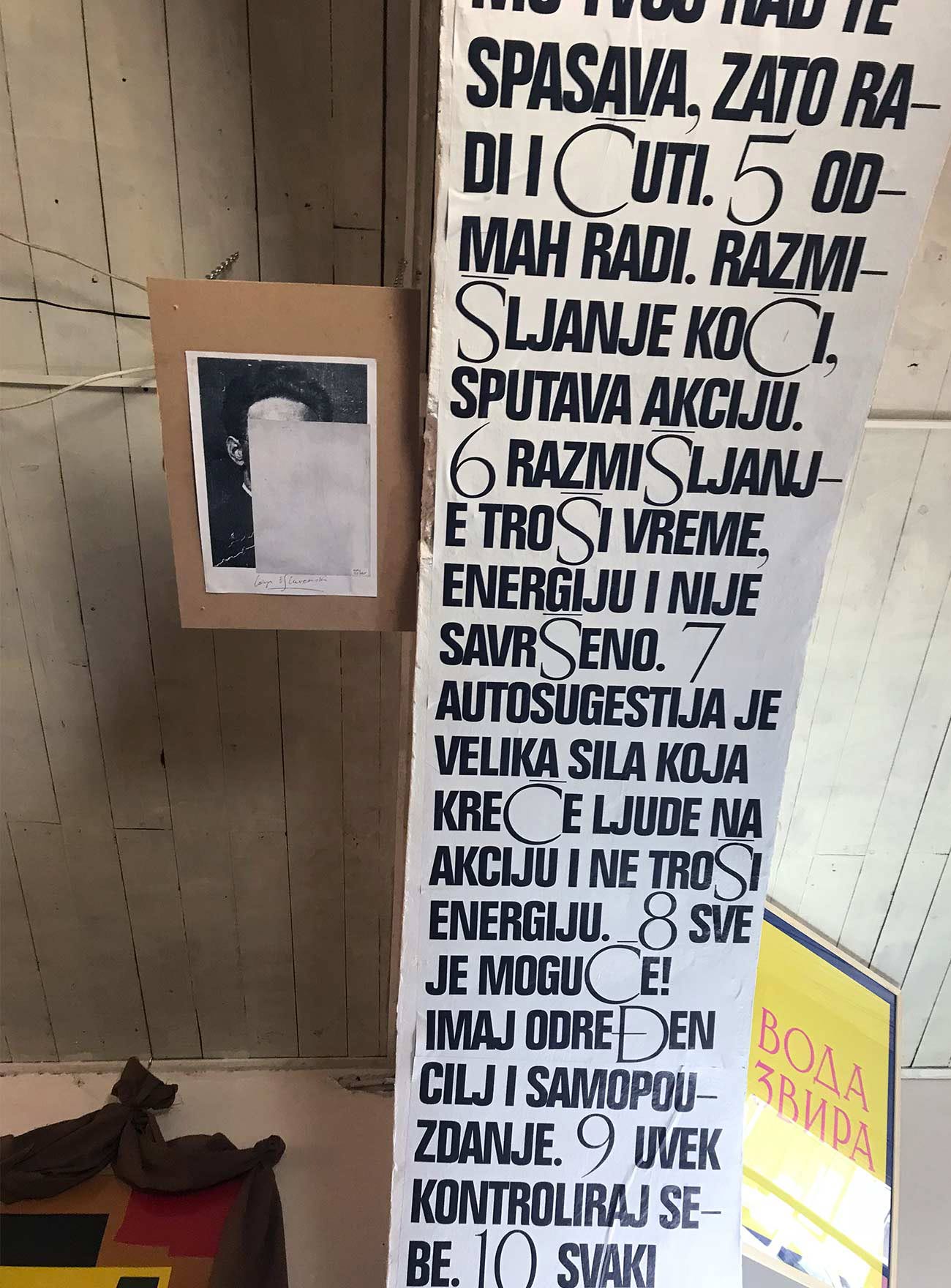

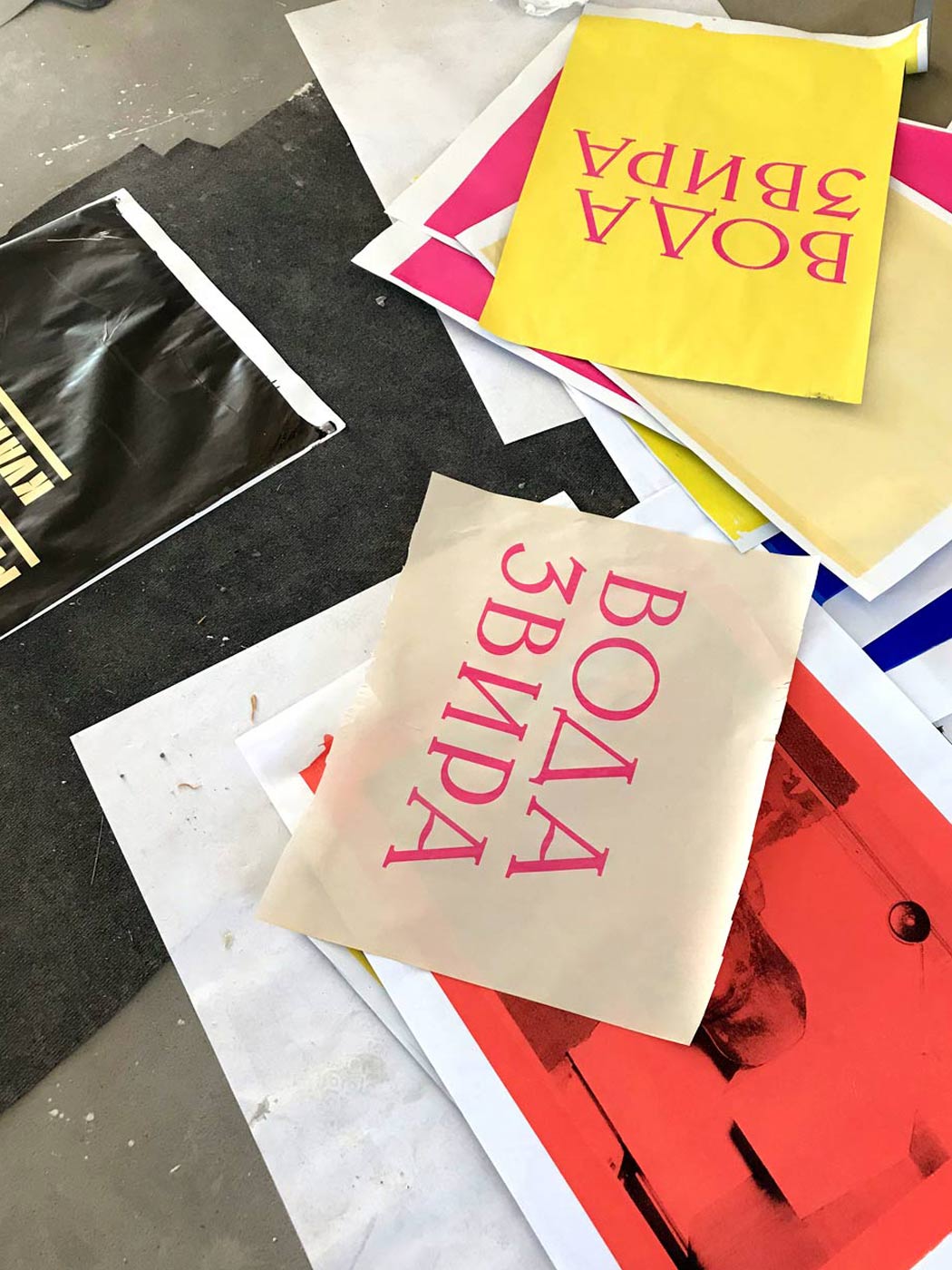

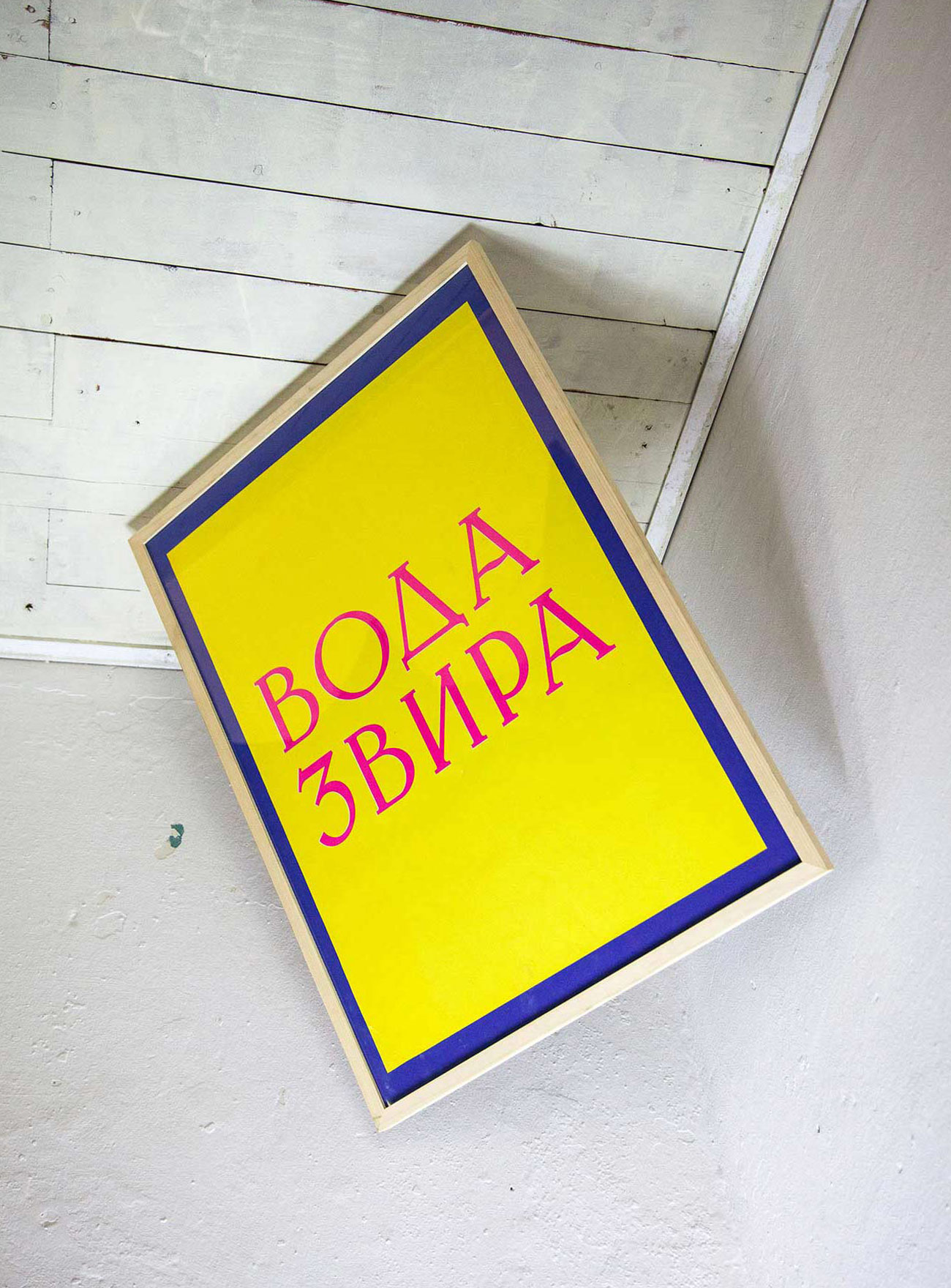

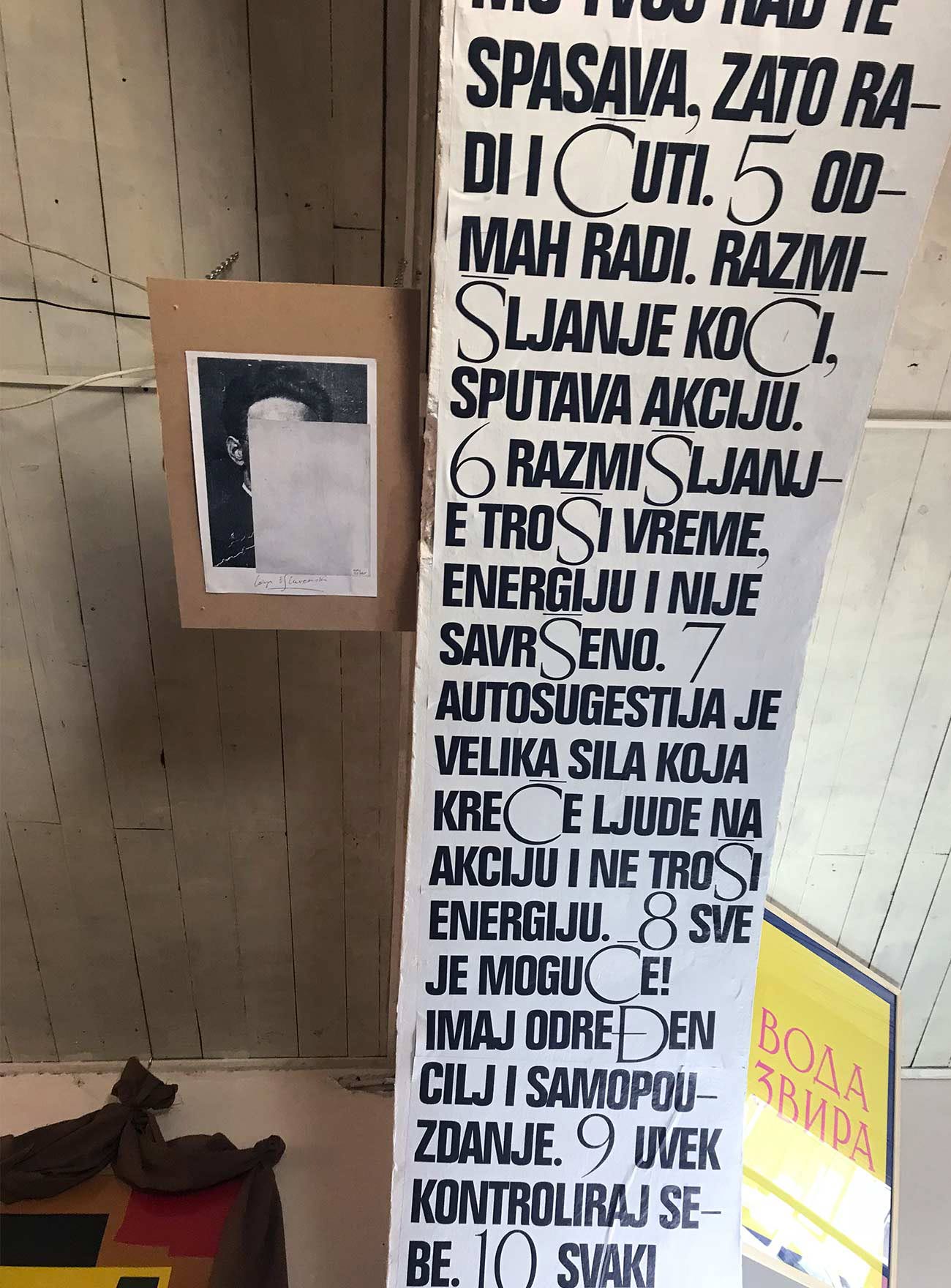

Be it an exhibition, workshop, concert or online presentation, every year I take a new approach with the aim of showing a work on that date that was inspired by him.

Accordingly, it is important to me to involve people from the fields of art and music in the project. To me it is essential to collaborate with museums, music schools, musicians, other events, musicologists, galleries and artists.

Josip Štolcer Slavenski – Composer of the Avanatgarde forever enamoured with the Balkans

Since autumn 2015 I have been researching the life and work of one of the most important and original Yugoslav avant-garde composers of the 20th century: Josip Štolcer Slavenski.

In addition to his impressive work, what fascinates me and spurs my research is the current treatment of Slavenski by today's successor peoples of Yugoslavia. Where other nations would praise a master like Slavenski, little attention is paid to him. Actually, he is hardly known.

Born in May 1896 into a modest Croatian baker’s family in the small town of Čakovec, at that time still part of Austria-Hungary, he developed his passion for music from an early age, supported by his mother.

After studying in Budapest at the renowned Zen Academia (1913–1916), where he was a masterstudent of Bella Bartók, and graduating from the Prague Conservatory (1918–1921), Slavenski moved to the roaring Belgrade of the 1920s.

Then the capital of the newly formed state Yugoslavia, colorful, noisy, full of colors of Balkan folklore and picturesque remnants of the East, Belgrade evoked in Slaveski unlimited passion and thirst for creation. One of his greatest works were created here, such as Balkanophonia, Sinfonia Orienta, Four Balkan Games, From Yugoslavia, Chaos аnd Songs of My Mother.

Performances at the global level followed, from Berlin, Buenos Aires and Tokyo through Athens, Budapest and Vienna to Venice and New York.

Since 2021, a website has been dedicated to Slavenski and his work.

He composed music for sound films of famous Prague and Berlin-based production companies, established contact with the renowned German publishing house Schott & Söhne and researched one of the first electronic music in general. Basically, he was one of the first to own a Trinitron, one of the first electronic devices that could produce music

In addition to music, he dedicated his time to science, especially astronomy, because he saw and searched a connection between cosmic currents and musical resonances. Slavenski even presented the theory of Astroakustics.

What is certainly most impressive and what makes Slavenski so unique is his approach: On one hand, Slavenski was very open to the social upheaval of European modernity, on the other hand, he was in love with the diversity and ancient folklore traditions and customs of the Balkan peoples. With this as a starting point, Slavenski created until then completely new and unusual works which, at first, meet with misunderstanding and often contradictory assessments by a large number of contemporaries.

With the end of the Second World War and the emergence of a socialist Yugoslavia, new ideologies were adopted with euphoria, which no longer fit into pre-war modernity on the one hand and the traditional Slavic approach on the other.

Works were created in the spirit of socialism, but he quickly withdrew and stopped composing. He died on November 30, 1955 in his home in Belgrade.

After his death there were attempts to revive his work, but that never reached the level Slavenski deserved. Most of these remained at the local level. With the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Slavenski was finally forgotten / consciously ignored. Because a man born in today's Croatia, who supported the empantipation and unification of the South Slav peoples and who spent most of his life in today's Serbia, did not fit into the concept of the newly formed states.

This dilemma of the forgotten maestro piqued my interest all the more. I began my research work in 2015 in Slavenski's hometown of Čakovec, where I got access to a considerable collection of his work at Međimurje County Museum. I later got in touch with the Serbian Music Association in Belgrade, which keeps and administers his entire legacy. As an artist, I don’t want to stop at theory or research, I started to organize an event every year for Slavenski’s birthday on May 11th.

Be it an exhibition, workshop, concert or online presentation, every year I take a new approach with the aim of showing a work on that date that was inspired by him.

Accordingly, it is important to me to involve people from the fields of art and music in the project. To me it is essential to collaborate with museums, music schools, musicians, other events, musicologists, galleries and artists.